Autumn breezes get voters thinking. That’s when they get serious about elections. And that’s when the pumpkins come out.

“Tons of pumpkins,” the handwritten sign boasted somewhere along the interstate.

John “Red” Heller had overstated it just a bit.

“Well, OK. Maybe it’s pounds and pounds of pumpkins,” Heller said, pointing to a truckload of the plump, orange symbols of autumn.

The unemployed construction worker had harvested his uncle’s patch the day before. He figures it’s the only money he’ll make this month.

“It’s getting chilly now, and that’s when people start buying these honeys,” Heller said.

An old political theory holds that voters turn conservative in the fall.

An old political theory holds that voters turn conservative in the fall.

Springtime months bring thoughts of change and renewal. Bicycle sales increase. People go on diets and clean house.

And the politics of change thrives.

Throughout presidential campaign history, third-party candidates and other rebellious hopefuls have peaked in the spring. That’s when Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump got on a roll.

Support for John Anderson in 1980 and for George Wallace in 1972 rose in the spring and dwindled in the fall.

Many springs ago brought the insurgent campaigns of Democrat Jerry Brown and Republican Pat Buchanan.

Ross Perot’s popularity soared in April.

But now the leaves are falling.

In this time for cocooning, Americans tend to look inward, cherish what they have and put off a search for change.

Heller, the pumpkin salesman, says he believes that it doesn’t matter anyway.

“Politicians never change things, do they?” the 37-year-old high school dropout said.

Before he could explain himself further, he turned his attention elsewhere.

A woman and her wide-eyed child had stopped to buy a pumpkin.

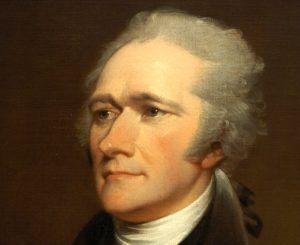

I was watching the Tony Awards in June and was enthralled watching Hamilton win award after award, totaling 11 by the end of the night. I’ve seen various snippets of the show on YouTube and heard most of the soundtrack. I’ve seen/heard enough about it to know it’s something that I’m interested in. I will definitely see Hamilton the moment any local theater group presents it, as I have done many times in the past for other shows. It won’t be the same cast, but the words and the power of the piece should be transferable to any theater production. It’s tough to be a Broadway lover when you can’t get to Broadway, but we make do.

I was watching the Tony Awards in June and was enthralled watching Hamilton win award after award, totaling 11 by the end of the night. I’ve seen various snippets of the show on YouTube and heard most of the soundtrack. I’ve seen/heard enough about it to know it’s something that I’m interested in. I will definitely see Hamilton the moment any local theater group presents it, as I have done many times in the past for other shows. It won’t be the same cast, but the words and the power of the piece should be transferable to any theater production. It’s tough to be a Broadway lover when you can’t get to Broadway, but we make do.